HISTORY

BEECHER BIBLE AND RIFLE COLONY

The Story of the Beecher Bible and Rifle Colony and the Sharps Rifle

When harsh winter weather put a stop to the violence between proslavery and free-state settlers in December of 1855, the free-state leaders returned to their previous homes in the east to raise money and hold public meetings in support of their cause. What became known as the Wakarusa War had started when a proslavery settler killed a free-state neighbor near Lawrence. It escalated into violent actions on both sides and the eventual siege of Lawrence by 1,500 proslavery Missourians. The conflict became known throughout the country as Bleeding Kansas, with newspaper headlines proclaiming “WAR IN KANSAS.” After hearing free-state leaders Eli Thayer and General Samuel Pomeroy speak at a meeting in New Haven, Connecticut, Charles Lines, a local cabinetmaker, was inspired to form a company of emigrants for Kansas. Meetings were held and the Connecticut Kansas Colony was organized. Lines was elected its leader.Meanwhile, the popular and eloquent abolitionist preacher Henry Ward Beecher, brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, was advocating arming emigrants to Kansas with Sharps rifles. The Sharps rifle, manufactured in Hartford, Connecticut, was the AK-47 of its time. It was vastly superior to arms available to proslavery forces.

Beecher was the leader of the congregation at Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, New York, but had been born in Connecticut and educated in Massachusetts. A number of the members of the New Haven Company were his personal friends and he took an active interest in their success.

Beecher was widely quoted as having said he believed that, “the Sharps Rifle was a truly moral agency, and that there was more moral power in one of those instruments, so far as the slaveholders of Kansas were concerned, than in a hundred Bibles.” This caused quite a stir, but he got even more national attention when soon after he published a pamphlet titled, “In Defense of Kansas.” In what we can now see as one of the most prescient statements in Civil War history, he wrote,

“A battle is to be fought. If we are wise, it will be bloodless. If we listen to the…counsels of men who have never shown one throb of sympathy for Liberty, we shall have blood to the horse’s bridles. If we are firm and prompt to obvious duty, if we stand by the men of Kansas, and give them all the help that they need, the flame of war will be quenched before it burst forth, and both they of the West, and we of the East, shall, after some angry mutterings, rest down in peace. But if our ears are poisoned by the advice of men who never rebuke violence on the side of power, and never fail to inveigh against the self-defence of wronged Liberty, we shall invite aggression and civil war. And let us know assuredly that civil war will not burst forth in Kansas without spreading. Now, if bold wisdom prevails, the conflict will be settled afar off, in Kansas, and without blows or blood. But timidity and indifference will bring down blows there, which will not only echo in our houses, hitherward, but will, by and by, lay the foundation for an armed struggle between the whole North and South. Shall we let the spark kindle, or shall we quench it now?”

While the Connecticut Kansas Company was preparing to leave for the prairies of Kansas, a meeting was held on March 20 at the Old North Church in New Haven. As the New York Times reported several days later, “the Church was filled—floor and galleries—with the most prominent citizens of New Haven, including a large number of clergymen of various denominations, and a full quorum of professors from the faculty of Yale College.” Charles Lines and Henry Ward Beecher made rousing speeches. Lines explained that the Sharps rifles that had been pledged by an individual for the colonists had already been sent to the territory to be used by General Pomeroy. He said that since members of the company had already gone to great expense outfitting themselves, he was making a public appeal for other weapons.

Beecher spoke about human rights and the differences between the North and the South, saying that the days of compromising two utterly irreconcilable elements were now over. He concluded his remarks by making an appeal to supply the colonists about to depart with arms for their defense. After loud applause, he sat down, and the audience sang John Greenleaf Whittier’s “The Kansas Emigrants,”—which is sung to the tune of “Auld Lang Syne.”

When the song was finished, Yale College Professor Benjamin Silliman stood up and said that self-defense in the cause of freedom is a sacred duty. Adding that he would like to be first on a list of pledges providing funds, he gave $25 for the purchase of one Sharps rifle. The pastor of the church, the Rev. Samuel Dutton, then stood proclaiming, “One of the deacons of this Church, Mr. Harvey Hall, is going out with this Company, and I, as his pastor, desire to present to him a Bible and a Sharps rifle.” Great applause followed and fifteen more pledges were made.

Beecher then rose and said that if funds for twenty-five rifles could be raised on the spot, he would pledge another twenty-five from his Brooklyn congregation. He then solicited bids from the audience in a jovial manner, saying after a Mr. Killam’s pledge, “that’s a significant name in connection with a Sharps rifle.” Soon twenty-seven rifles were pledged, including two from the junior and senior classes at Yale.

According to a New Haven historian, “Such an extraordinary meeting had never been held in an American church, and its proceedings were heralded all over the land, producing from the pro-slavery press a storm of unmitigated denunciation and abuse.”

When Beecher sent a check to Lines honoring his pledge for twenty-five rifles he included with it twenty-five Bibles and a letter meant for publication. When he was raising money to fulfill his pledge he wrote to the cousin of a friend in New Jersey saying,

“I am making up a pledge to furnish the men of my native state, Connecticut, with means of self defence when they are too poor to supply themselves, and if you are willing to aid in the great work I should be glad to have help. We are going to present a Bible with every one of the defensive arms, — and put upon the covers, BE YE STEADFAST, UNMOVEABLE.” The letter that accompanied the check and the Bibles was widely reprinted in newspapers across the country under the headline, BIBLES AND RIFLES FOR KANSAS and BIBLES AND RIFLES IN KANZAS. It was from these events that the company began to be referred to as the “Beecher Bible and Rifle Colony” and the Sharps rifle took on the nickname “Beecher’s Bible.”

CAPTAIN WILLIAM E. MITCHELL BY KATHRYN MITCHELL BUSTER

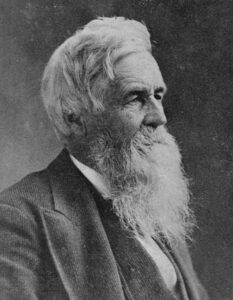

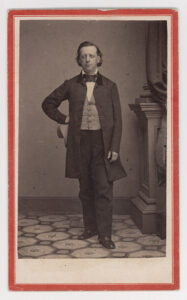

Captain William E. Mitchell, Jr. was born in or near Kilmarnock, Scotland on June 24, 1825, the son of William E. and Mary Izott Mitchell. William, Sr. was thought to have been a weaver in or around Paisley, Scotland.

Capt. Mitchell’s siblings were Alexander, Agnes, Jean, James, and possibly even Henry and a sister, Helen, who may have died as a child.

In 1826, when William was just one year old, his family immigrated to Middletown, CT where his father was weaver in charge of the Russell & Company Weaving Mill in Middletown. His father was also very active in the Middletown Anti-Slavery Society, which was founded in the 1830s.

Young William was educated at D.H. Chase’s private school in Middletown. He then served as a corporal in the Connecticut State Militia in 1846. In 1849, he embarked on a six-year odyssey in search of gold, sailing from New York City to California via Cape Horn. It is assumed that he was not successful, for in 1852 he traveled on to search for gold in Maldon, Australia. After a six-year absence, William returned to Middletown, making a detour on the way home to visit family in Scotland.

When William returned to the United States, he found a country embroiled in controversy over the question of slavery and the newly enacted Kansas-Nebraska Act which gave settlers in these two territories “popular sovereignty” to decide for themselves whether they would enter the Union as free or slave states. At that time the Connecticut-Kansas Colony was being formed in New Haven, CT, recruiting people to settle in Kansas Territory to ensure its future as a free state. With his abolitionist upbringing and apparent wanderlust, William was eager to join them.

The Connecticut-Kansas or New Haven Colony is also referred to as the Beecher Bible and Rifle Colony. The great abolitionist preacher Henry Ward Beecher, in rousing oration, led a drive to furnish a Sharps rifle, the most modern weapon of the day, to every member of the Colony immigrating to Kansas Territory. He also saw that a Bible was given to each man. And with that, the newspapers of the day began to refer to the group as the Beecher Bible and Rifle Colony, and the rifles as Beecher’s Bibles.

When the Colony left Connecticut their members included fifty-seven men, four women and two children. They traveled by boat to New York, and by train to St. Louis via Buffalo, Cleveland and Terre Haute. At St. Louis they boarded the steam ship ‘Clara’ for Kansas City.

Charles Lines, the company’s elected leader, kept a diary of their progress in the form of letters sent to Eastern papers. They were widely reprinted and circulated so that the entire country was aware of the Colony’s experiences in Kansas.

When they arrived at Kansas City they bought supplies and outfitted themselves with teams of oxen, then started in groups for Lawrence, arriving there between the 12th and 16th of April. G.W. Brown, editor of the Herald of Freedom, wrote of their arrival, “ They are a hearty, resolute, freedom-loving looking set of fellows, and we wish their fondest anticipations of life in the West be fully realized.”

On the evening of the 15th a meeting of welcome was held by the town’s leaders. Speeches were made and friendships re-kindled and initiated and the Company was invited to join in the Free State Government (within weeks Free-state leaders were arrested for treason and colony member Dr. Joseph Pomeroy Root was elected Chairman of the Kansas State Central Committee). The colonists pledged to come to the aid of Lawrence if called.

On the evening of the 18th, the company joined the citizens of Lawrence welcoming Senator Reeder and Free-State Governor Robinson in the dining room of the unfinished Free State Hotel. Ex-Governor Reeder and Robinson had been away when the town celebrated the Colony’s arrival. Pro-slavery forces would destroy the Free State Hotel during the sacking of Lawrence the following month.

After exploring other possible locations, the entire company arrived at Wabaunsee on the 28th of April and set about making it a home, their first shelters being dugouts or tents. Charles Lines suggested they all work together to build one large communal dwelling from the scarce supply of cottonwood trees growing on a nearby island in the Kansas (Kaw) River. Mitchell declared he would have none of that, and built himself a small log cabin three miles east of Wabaunsee.

According to Company minutes, on May 14th, “Mr. Lines called a meeting and read a dispatch from Topeka; “Dear Sir, news has just come that colonels Holliday, Dickey and Governor Robinson are now prisoners with the Missourians and that our friends at Lawrence are in want of help. Hope you will all come to a man and bring all the spare arms you have—come immediately to Topeka and there we will devise the best plan for operation.”

Adding to the urgency of this call for help, Colony member Amos Cottrell was overdue to return from Kansas City with a load of freight, so they decided to dispatch Mr. Mitchell, Dr. Root and Mr. Nesbitt to locate Cottrell and find out what was going on in Lawrence, and to report as early as possible. After the committee’s departure the Company voted to organize a military company they named the “Prairie Guards.” The absent William Mitchell was elected their Captain. They were enrolled as Company H. of the Free Kansas Militia. William Mitchell was addressed as Captain for the rest of his life.

The trio found Cottrell safe at Topeka, and Mitchell and Root continued on to Lawrence to assess the situation there. Having done so, they were on their way back to Wabaunsee on the California Road when they were fired upon as they approached a cabin occupied by the Lecompton Riflemen under the command of Captain John Donaldson. Placed under arrest without charges, they were taken to Dr. Stringfellow’s camp (probably Fort Titus) the next day. Sara Robinson documents the incident as an act of lawlessness in her book, Kansas: It’s Interior and Exterior Life. Eastern papers, including the New York Times, reported Mitchell and Root’s deaths at the hands of border ruffians. On the sixth day of their captivity, the 21st of May, they were marched within two miles of Lawrence where they witnessed David Rice Atchison address the assembled pro-slavery forces before their sacking of Lawrence. Dr. Root, who was proficient at shorthand, recorded Atchison’s words for posterity:

“Carry out to the letter the lofty and glorious resolves that have brought [you] here—the resolves of the entire South, and of the present administration, that is, to carry the war into the heart of the country, never to slacken or stop until every spark of free-state, free-speech, free-niggers, or free in any shape is quenched out of Kansas!”

The prisoners were released as the bombardment of the Free State Hotel began. Mitchell and Root returned to Wabaunsee the next day.

On June 30th Mitchell and two others were elected to represent the company at the Free State Convention called at Topeka for July 3rd. Dr. Root was there in the role of Chairman of the Free State Executive Committee. Root and Mitchell were present when the gathering was dispersed by federal troops the next day.

Later that summer the Wabaunsee Prairie Guards were called to participate in the fall campaign. They were gone for six weeks and participated in a number of skirmishes against pro-slavery forces under the command of Jim Lane and others. They manned breastworks on Mount Oread and were credited with saving the day when the “largest and best organized band that had ever invaded the territory” was massed at Franklin preparing to attack Lawrence. Known to veterans of the Border War as the September 14th “Battle of the 2,700”, and considered “one of the most critical situations of the war”, it occurred when most Free-state forces were away fighting the Battle of Hickory Point near Valley Falls. The “Wabaunsee Boys”, with their Sharps rifles, stayed in Lawrence because a number of them were sick. Remembering the day, colonist J.M. Hubbard described the scene:

“In the midst of the excitement and confusion of the situation, old John Brown appeared upon the scene and proceeded to advise and direct with all the coolness of a farmer going about his evening chores.”

“The whole body of border Ruffians were in camp at Franklin. They were seen coming on the main road into Lawrence; the Beecher Rifle Company took a position about a half a mile out of town in a ravine and when the column came in shooting distance our boys opened fire on them. They soon turned back and got out of range of the Sharps rifles. It was the Wabaunsee boys and they alone that turned that body of men back in double-quick time.”Fortunately for Lawrence, the newly appointed Territorial Governor Geary traveled in the night from Lecompton to Franklin and was able to convince the pro-slavery forces to stand down, and the anticipated battle did not happen.

After his mother’s death in Middletown in 1858, Capt. Mitchell invited his father and his unmarried sister Agnes to come live with him. It was during this time that Capt. Mitchell was active as a “conductor” and “Stationmaster” on the Underground Railroad, hiding freedom-seekers in the loft of his log cabin.

In response to the destruction of Lawrence led by the Confederate Guerilla leader William Quantrill on August 21, 1863, Governor Carney placed the state on a war footing and called for all able-bodied men to organize themselves into militia companies. The Prairie Guards had disbanded when the territory attained statehood in 1861. The Wabaunsee men met on September 12th at the town hall and formed company C, of the Fourteenth regiment. William Mitchell was elected a second lieutenant, but was later appointed to a staff position.

As George S. Burt later recalled, “We began drilling, as nearly every one had some kind of a horse, and some of the mounts were truly ludicrous. We held quite a number of meetings before all the able-bodied men were in line. We met to practice every Saturday afternoon, going through the common cavalry maneuvers. Captain Noyes had been in the three months’ service at the beginning of the war in 1861, so he knew a few of them. We continued to practice through the fall and into the winter, as the people were not rushed with work, and there was no objection to those who had no horses coming to look on.

When spring opened we did not meet very often, and had begun to think that there would be no call for the militia, but all at once, in July 1864, a call came one Sunday morning to the captain to get every available man who had a horse, and proceed to Fort Riley at once. The Indians had attacked a wagon train near the great bend of the Arkansas river, killed some of the drivers, and stole goods, cattle and horses, and had escaped into the hills northeast of Fort Larned.”

“At Junction City we were joined by the Pottawatomie and Riley County companies; also the Zeandale company, with Perry McDonald as captain. J. M. Limbocker was captain of the Riley county company. Here we were all put under the command of Capt. Henry Booth, of company L, Eleventh Kansas Cavalry, who was going west after the Indians.”

They marched as far west as Trego County and were gone from home about three weeks. They never engaged any hostile Indians.

Capt. Mitchell’s father died in 1864 and is buried in the Wabaunsee Cemetery. Agnes Mitchell stayed on after their father’s death, to keep house for her brother until his marriage in 1868 in Cleveland, Ohio, to Mary Ann Chamberlain (who was originally from Middletown, CT as well). During this same time (1868-69), Capt. Mitchell served as a State Legislator, helping write Kansas law.

The Mitchells had four children in those early years. Alexander C. (Chamberlain?) was born in 1869, H. (Henry?) Raymond in 1872, William Izott in 1873 and Maude Josephine in 1875.

Before his marriage, Capt. Mitchell, using the log cabin as a nucleus, expanded the house to one more suitable for a bride from the East. As the family grew, the house grew. (Due to its history as a way station in the Underground Railroad, the house is now a Freedoms Frontier National Heritage Area partner and an authenticated site in the National Park Service’s Network to Freedom program commemorating the Underground Railroad).

The family lived in the house and farmed until 1881 when Capt. Mitchell found a manager for the farm and moved his family to Wabaunsee. For the next 14 years, he and his sons ran a general store in Wabaunsee, which also served as the U.S. Post Office and the depot for the Santa Fe Railroad. In 1895, those of the family still at home, returned to the farm, where Capt. Mitchell lived and farmed until his death in 1903. He is buried in the Wabaunsee Cemetery. In 1953 his son Will bequeathed a portion of the Mitchell farm to the people of Kansas to become a public park commemorating his father and the Beecher Bible and Rifle Colony. The property is now known as the Mount Mitchell Heritage Prairie Park.

JOHN CHARLES FRÉMONT AND THE TOPEKA FORT RILEY ROAD

The origins of the old road that descends from the Flint Hills down the eastern flank of Mount Mitchell will probably never be known. Trailblazer Jedediah Smith may have been the first American to use the trail during the 1820s. This route West, on the south side of the Kansas River, became known for its ease of passage because it kept to the high ground and avoided having to cross streams.

In 1842 Congress authorized a survey of the Oregon Trail, the main route of westward emigration between Missouri and Oregon and California. John Charles Frémont was made leader of the expedition.

The mountain man, Kit Carson, was Frémont’s guide on this and other expeditions between 1842 and 1846. The 1843 expedition most likely used the trail that traversed Mount Mitchell.

When Fort Riley and Topeka were established in 1853 and 1854, this old reliable route began to be called the Topeka Fort Riley Road. A popular stage line advertised it as the “Nearest and Best Route between Fort Riley and the eastern part of Kansas.”

Between 1857 and 1861, enslaved people seeking their freedom in Canada, used this road on what was probably the westernmost branch of the Underground Railroad. A dramatic account by Charles Leonhardt called The Last Train documents an 1860 trip along a route that traveled up the Wakarusa, to Bloomington, Auburn, and the Harvey Settlement. From there it went northwest, joining the Topeka Fort Riley Road near present day Paxico, then on to Wabaunsee. After crossing the Kaw River they continued on to Centralia, eventually joining the Lane Trail at Nebraska City.

Today, this portion of the trail is recognized by the National Park Service as an authenticated Underground Railroad Site in their commemorative Network to Freedom Program.

Visitors to Mount Mitchell can stand in the ruts of this historic road and imagine the stories of those who passed over it.

BEECHER BIBLE AND RIFLE CHURCH

Until 1854, when Kansas was opened for settlement, the spot on which this old landmark church stands was just part of a vast ocean of tall prairie grass, under the ever-changing skies. To the north lay the Kaw River, crowding the bluffs beyond. A few miles to the east stood hills of spectacular beauty, and the prairie rolled gently away toward the south and west. The silence was broken only by the winds or by the song of a meadowlark, and at night by the music of the prairie wolves. The land belonged to the Indians, to the roving herds of buffalo and antelope, and to the great flocks of migratory birds.

The Kansas-Nebraska Bill, passed in May, 1854, changed all this forever. It provided that Kansas could become a free state or a slave state, depending on how the people of Kansas voted. The race was on to stake out claims, and to vote Kansas “free,” or “slave.”

Two years later, in 1856, there were already about sixty people living within a few miles of this place that they called Wabaunsee, an Indian name meaning “Dawn of Day.” Here, on the south bank of the Kaw River, 100 miles west of Kansas City, a settler had built a tiny store.

In New England, “Kansas Fever” ran high. The people of New Haven, Connecticut, raised money to send a group of colonists to Kansas; fifty-seven men, four women, and two children. Led by one of New Haven’s most respected citizens, Charles B. Lines, these were well-educated men, many with professional training. They left good jobs and good homes behind them. They were not just adventurers, with little to lose by going west; they were men making a sacrifice for their ideals.

Before the Connecticut-Kansas Company left for Kansas, a meeting was held in North Church, in New Haven. Professor Silliman, of Yale, pledged $25.00 for a Sharps rifle for the Company. Then Henry Ward Beecher, the great minister from Brooklyn, NY, pledged that his congregation would give the money for twenty-five rifles if the audience would give another twenty-five; people in the crowd responded in great excitement, and soon twenty-seven had been promised. A few days later

Mr. Beecher sent Mr. Lines $625 for the rifles, and with the money came twenty-five Bibles, the gift of a parishioner.

The company left New Haven at midnight, on March 31st, after a torchlight parade across town to the steamboat to New York. The next day they were on a train to St. Louis, a three-day journey of great discomfort. From St. Louis they sailed up the Missouri River on the steamboat Clara, as far as Kansas City. There they bought thirty wagons and sixty oxen, along with farm implements, tents, and provisions for thirty days. They started west on the Oregon Trail, stopping for a few days in the Free-state town of Lawrence, where they were welcomed by Free-state leaders. After visiting Mission Creek, west of present-day Dover, they continued along the trail to Uniontown, near what is now Willard. Here, instead of following the trail across the Kaw River, they veered left and continued west, south of the river, until they reached the place their scouts had selected, Wabaunsee, “The New Haven of the West.”

In late April 1856, (almost a month away from New Haven) Wabaunsee suddenly became a busy tent city. Streets were laid out, and city lots and tracts of prairie land were divided among the men of the Company. The settlers already on the scene welcomed the New Englanders, and some of them joined the worship services that were held on Sundays, first in tents, then in cabins or dug-outs. The new settlers found pioneer life very hard. Some became ill or discouraged and returned home.

Those who remained until August were then called to go to the defense of Lawrence. Organized as “The Prairie Guards,” under their elected captain, William Mitchell, they spent six weeks fighting the border-ruffians.

The winter of 1856-57 was one of suffering in Wabaunsee, but things seemed more hopeful in the spring, when the wives and children came to join the men. Now that a permanent settlement seemed assured, there was a desire for a permanent church organization.

In late June 1857, fifteen of the members of the Colony and thirteen other settlers met to organize “The First Church of Christ in Wabaunsee,” with the Rev. Harvey Jones as Pastor.

Of this group of twenty-eight charter members, nine were women. After two years of raising funds for a church building, mostly in New Haven, they started construction of the sturdy stone church-that still stands in Wabaunsee.

The stones were hauled from nearby quarries, on sleds drawn by oxen. The mortar was mixed by hand, and the long shingles, called “shakes,” were made with crude hand tools. The rows of straight-backed pews were divided down the center of the church by a low wooden partition that separated the men from the women.

From the balcony across the rear of the church, a ladder led to the belfry. The church-yard was edged with hitching posts, and there were newly planted trees and lilacs in appropriate spots.

The new church was dedicated in May, 1862. By that time some of the members had already gone to fight in the Civil War. Soon there were only a few boys and older men to carry on the work in Wabaunsee. But after the war was over the town began to grow again. It never became the great city the people from New Haven had envisioned, but the area grew into a thriving farm community.

The church became one of the largest and most influential Congregation churches in Kansas. Only a few of the Connecticut families remained to bring up their children in Wabaunsee, but those few were a strong influence there, and in Kansas.

The pioneers of Wabaunsee sent their children to Washburn College or to Kansas State Agricultural College, to become teachers, ministers, or missionaries. These young people then went to far places in the world to work, but they never forgot Wabaunsee.

When the church needed repairs they always gave generously to assist the Willing Workers Society, that group of church ladies forever busy with ice cream socials or oyster suppers given to raise money to help pay the minister’s salary or the mortgage payments on the parsonage.

In 1907, old friends of the church came from far away to help celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the First Church of Christ in Wabaunsee. Only two of the original Company still lived in Wabaunsee then, but they both played a large part in the Jubilee celebration.

In 1913, there was a renewal of interest in the church when a new minister came to start an experiment in rural development. The Rev. Anton Boisen, later to become a very famous man, organized the people to build sidewalks, improve the churchyard and the cemetery, and to better their economic and social lives.

But the population of the area was dwindling, and so many people left, as an indirect effect of World War I, that after 1917 it was no longer possible to keep a resident minister. After that there were guest ministers from time to time, and services held with the Methodist church of Wabaunsee. An effort was made to federate the two churches, but this failed, and soon the old stone church was practically deserted. The last entry in the official record book was made in 1927.

The descendants of the “Beecher Colony” organized “Old Settlers Association” in 1932. The last Sunday of August was designated “Old Settler’s Day by the Association.

Throughout the years “Old Setters” gathered on this day as well as Decoration Day to reminisce and to honor men and women who had made that church a symbol of freedom around the world.

Homecoming continues to be celebrated on the last Sunday in August. Former members spent more than one thousand dollars in the renovation of the Church in 1948. This same group, a few years later, raised a similar sum to erect a monument gate for the Wabaunsee Cemetery entrance. The gate was designed by Maude Mitchell, the daughter of William Mitchell. He was the captain of the “Old Prairie Guards.”

In 1950 residents of Wabaunsee formed a new church group, and began to hold weekly services. This was said to be the first inter-racial Congregational Church in Kansas, a fact which impressed many as a fitting tribute to the Connecticut-Kansas Colony.

The Church’s Centennial, in August 1957, saw the old building much as it had looked when completed, almost a hundred years before. The old pews were still uncomfortable, the floors still dark and creaky, and the windows still tall and narrow. But a year later much had been changed.

A youth group, under the sponsorship of the Kansas Pilgrim Fellowship, spent two weeks in Wabaunsee renovating the building with members of the church. They put in a new floor, a tile ceiling, and replaced the old coal stoves with modern heaters. Soon after that, the parishioners of a church about to be inundated by the waters of Tuttle Creek Reservoir donated its pews to replace the old ones in the Wabaunsee church.

More recently stained-glass inserts have been placed in the old windows. Sunday Worship Service and Sunday School are conducted each Sunday. Continuation of these services dates back to 1950. Since this time these services have been conducted by full time and part time ministers, special guests, and laypersons.

The congregation continues to welcome guests, guest speakers, new and old members. In 1992, The George Thompson Christian Center was built. This building has modern facilities for Sunday School classes and other activities. This church has been servicing the public since 1862, although not continuously.

In the park, a few blocks north of the church stands a monument erected by the Kansas State Historical Society. On it are carved these words:

“In memory of The Beecher Bible And Rifle Colony, Which Settled This Area In 1856 And Helped Make Kansas A Free State. May Future Generations Forever Pay Them Tribute.”

MAUDE J. MITCHELL (1875-1957)

Maude Josephine Mitchell was the daughter of early Wabaunsee County pioneers Captain William and Mary Mitchell. Captain Mitchell was a leader of the Beecher Bible and Rifle Colony who came to the area in 1856. He operated an Underground Railroad station at his home three miles east of the town of Wabaunsee.

Maude Mitchell received her early education at district school number two in Wabaunsee County. She attended the New York State Normal College at Buffalo, New York. After graduation, Mitchell taught district school near Manhattan, Kansas. She then went to New York City to study art at Columbia University. She also studied at the Art Students League in Manhattan and Woodstock, New York.

Mitchell served as an art supervisor in the public schools of Dubuque, Iowa. She led the art department of the Platteville State Normal School in Wisconsin for thirteen years.

In 1915, her mother passed away, and she returned to Kansas to take charge of the Mitchell Ranch.

Continuing to paint, Mitchell became a well-known Kansas artist. She exhibited her work in regional exhibitions, including those in Kansas City and Topeka.

Many of Mitchell’s paintings present views of Pottawatomie and Wabaunsee counties. The artist sought to preserve the architecture and landscape around her in impressionistic watercolors and oils. Her favorite subjects were the farms and outbuildings of her neighbors and Flint Hills landscapes. A few of the artist’s works touch on the story of black settlement in post-Civil War Wabaunsee County. Three known works depict the homes of former slaves.

Many area residents took art lessons from Mitchell. Some of her former students are still painting in the Wamego area.

Occasionally Mitchell traveled to Florida to spend the winter with her brother, Raymond, at Clermont. These journeys inspired several Florida landscapes.

Mitchell was also a musician and composer. Among her published works were such tunes as “Prairie Roads a Winden” (recorded by Roy Rogers), “The Dance of Romance,” and “Ridin’ in the Rain.” The artist’s other accomplishments include a series of murals for Columbia University and the design for the stone gateway at the Wabaunsee Township Cemetery. Mitchell’s poetry, editorials, and cartoons were published widely. She had an interest in public affairs and a wide circle of friends. Mitchell was a leader among those who have sought to preserve and make vital the history and culture of Wabaunsee County.

An exhibition titled, HOMESTEADS OF THE FREE: THE ART OF MAUDE J. MITCHELL sponsored by the Mount Mitchell Prairie Guards and the Wabaunsee County Historical Society was held at the Society’s museum in Alma in June and July of 2011.

WILLIAM IZOTT MITCHELL

William I. Mitchell, known to his family as Will, was born September 11, 1873, in Wabaunsee, KS, the third son of the ardent abolitionist, and leader of the Beecher Bible and Rifle Colony, Captain William E. Mitchell (1825-1903) and Mary Ann Chamberlain Mitchell (1836 or 37-1915). His siblings were Alexander C. (1869-1955), Henry Raymond (1872-1961), and a sister, Maude Josephine (1875-1957).

Young Will grew up on the Flint Hill prairies of the brand new Free State of Kansas. As a child he listened to his aunt Agnes tell stories about her and his father’s participation in the Kansas Underground Railroad. He later recounted these stories in his memoir and in a letter to historian Wilbur H. Siebert.

In 1884 he attended the 30th anniversary celebrations of the settlement of Kansas at Bismarck Grove in Lawrence. He remembered hearing his father and Doctor J. P. Root discuss a plot by Missourians to attack the Beecher Colony when it docked at Lexington on its way to Kansas in 1856.

Will attended the local one-room schools, had grand adventures with the other boys of Wabaunsee and got into his fair share of scrapes. He was obsessed with “modern” farm machinery and with trains, riding on the inaugural run of the Manhattan Alma and Burlingame Railway on July 5th 1880, when he was only six years old. He and his two older brothers were also avid and formidable baseball players, competing with teams from other small neighboring towns.

From a very young age Will was assigned lots of farm and home duties and, when he was 18, he was given sole responsibility for running the family “store” which was a combination of Santa Fe Railway Station, general store and post office. His first “real” jobs were on the railroad, progressing from loading freight to acting as station cashier in various towns in Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas.

Life wasn’t all work, however, as he was able to attend the Columbian Exposition (Chicago Worlds Fair) in 1893 where he spent all his time in the buildings housing new technology. During a “slow time” in 1896, Will undertook a trip from Wabaunsee to Buffalo, N.Y. and back on his beloved “wheel” (bicycle). He describes all the adventures of the trip in detail in his memoir. After his return to Wabaunsee, Will attended college for a year at Kansas State Agronomy College (now KSU) in nearby Manhattan, KS, before going back to work on the railroad.

In 1902, Will and his older brother H.R. were offered jobs at the New York Zoological Park (now the Bronx Zoo), which was just being established by their uncle, William T. Hornaday. (Hornaday was a noted zoologist, taxidermist, author, zoo director and founder of the American conservation movement.) Except for a two-year period when Will quit and tried a variety of other jobs in an attempt to earn more money for his growing family, he worked at the zoo until he retired in 1940.

Through his Uncle William Hornaday and Aunt Josephine Chamberlain Hornaday, Will met a lovely young red-haired lady who was working at the New York Botanical Garden, just across the street from the zoo. Palmyre Louise de Chateaudun Clarke had moved to New York after spending some years in Sweden where her mother was married to a member of the Swedish peerage. Will was smitten. He courted and won “fair lady’s hand” and they were married on Thanksgiving Day in 1904. Their marriage appeared to be one of true love and deep devotion, which lasted throughout their lives.

Over the years the Mitchells owned two different homes in New York City, one in the Bronx and then one in Yonkers near the zoo. Palmyre and their children, Marguerite Palmyre (Sallie) born 1906 and William Hamilton (Mike) born 1907, spent summers at their beloved summer cabin “Solbakken” in the forested hills of Montague Township, N.J. In spite of his love of all things mechanical, Will didn’t learn to drive until he bought his first car when he was 47 years old — a used Dodge Sedan for $750. The previous owner showed him the brake and the gas, and Will found himself driving it home through New York City! After that, the family began taking camping auto trips into New England to research family history and genealogy and visit old family and historical sites. They also made auto trips to Detroit to get new cars “at their source,” as well as train trips to California to visit Palmyre’s family and, in 1915, to attend the Pan American Fair in San Francisco.

As previously mentioned, Will retired from the New York Zoological Gardens in 1940, after 37 years of service there. In 1951, when he was 78 years old, he began writing his memoirs, a task which resulted in three fascinating volumes. He was not quite finished when he died in 1953 in Yonkers, N.Y.

His ashes were buried in the Wabaunsee Cemetery. In his will he left a portion of his parent’s farm to the Kansas State Historical Society to become a public park dedicated to his father, Captain William Mitchell, and members of the Beecher Bible and Rifle Colony. His will stipulated that the park be called “Mount Mitchell” presumably because in his mind ‘mount’ gave more stature to the site. The historical society was unable to develop the park he envisioned, but fortunately, in 2006, his descendants and local residents were able to make his wish a reality when the Mount Mitchell Prairie Guards established the Mount Mitchell Heritage Prairie Park on the property. Today it is a popular attraction known for its history and intact tallgrass prairie.

DODGE FIELDING (1917-1945)

George Temple Fielding, III, called “Dodge”, was the grandson of George Temple Fielding, pioneer businessman and two-time mayor of Manhattan, Kansas. He was a cousin of the William Mitchell family, who owned Mount Mitchell. Captain Mitchell’s wife, Mary Chamberlain Mitchell, had a sister, Josephine, who married William Temple Hornaday, the famous pioneer environmentalist and founder of what is now the Bronx Zoo in New York. Their only child, Helen, married George Temple Fielding II, and they had three children, George, Lorraine, and Temple Hornaday Fielding. Temple was the author of the widely used Fielding’s Guide to Europe. George was a 1939 graduate of Princeton University, where he received honors as an ROTC cadet. When World War II broke out he enlisted and was sent to the Pacific Theatre where he was killed in action. The following tribute was written by his brother Temple.

Alma Signal Enterprise June 5, 1947

The members of Ed. Palenske Post No. 32, of Alma, had charge of the Memorial Day services at the Wabaunsee Cemetery.

After the Wabaunsee services the thirty-two members of the Post present went to the Mitchell farm in Wabaunsee township, where a stone with bronze tablet had been erected to the memory of Captain George T. Fielding III, who was killed in action at Luzon. The monument was dedicated by the Legion to all service men who lost their lives in the war, and to Captain Fielding.

The following story was written by Temple Fielding, a brother of Captain Fielding, but was received too late for publication Memorial Day:

In his early boyhood, one of life’s greatest adventures for George was to return to the land of his people. Grandfather Fielding was several times Mayor of Manhattan, a pillar in the community; Father Fielding was a proud graduate of the wheat fields, the local schools and the State College. They were Kansas. By blood and choice, so was young “Dodge.”

It was 1926 when he made his boldest expedition. He was passing his second summer at the Big Four Ranch [the Mitchell farm] near Wamego, a quiet earnest boy of ten. Miss Maude Mitchell, his cousin, packed a lunch for the pirates—Junior Bright, age nine, was his companion—and together they trudged across the road and up the steep hill, which smiles over the countryside. As an afterthought, Miss Mitchell tucked a ten-cent bag of clover seed into their parcel.

They spent a long day on top of their mountain, searching for arrowheads, playing Captain Kidd, munching sweet drumsticks from the lunch box, watching the wind in the golden sea below. Dodge planted the clover with tender care; Junior sunned himself on a rock and made up yarns about the cotton clouds. Before darkness fell, they returned to the farmhouse, happy in the accomplishment of their perilous mission.

As the years passed, Dodge grew away from the soil, but he never forgot it. Eastern schools claimed him. He graduated from Princeton with Highest Honors in 1939. The University gave him the White Cup, a symbol for performance in the ROTC; they knew a soldier when they saw one.

In battle, percentages too often run out. He volunteered for the National Guard in 1940, and during his three years in the Pacific he fought as a forward observer, survey officer, and reconnaissance officer—the riskiest assignments in Field Artillery. At Munda he was personally commended by Lt. General Harmon, Supreme Commander of the invasion; in New Guinea he was awarded the Bronze Star; later he was recommended for the Legion of Merit. But no soldier can land with the first wave forever; his chapter was closed when a Jap grenade exploded during the last major campaign of the war.

Twenty-one years is a lifetime to many men, but to clover it is a fleeting second of time. The seeds this youngster planted multiplied with two decades of passing seasons. On top of the hill there now stretches a soft rich blanket, a blaze of color which can be seen from miles around. The American Legion men of Alma were there on Memorial Day; so was “Aunt Maude,” Hal Weaver and other friends.

The surviving members of his family—Connecticut, Michigan, New York, California, and five other states—have chosen this flowering hilltop as the site most suitable as a living memorial. On a large rock in the center of the pink patch was placed a bronze tablet. It says:

Captain George T. Fielding III. 192nd F.A. Bn., 43rd Div., U.S.A. Killed in Action near Manila. P.I. April 30, 1945. Aged 28 years.

Then simply and quietly, “In memory of Dodge—Doer of Good Deeds.”

Because the memory of Dodge and our thousands of Dodge’s will live as long and spread as heartily as the Kansas clover.

The Park is open year round, dawn to dusk. Removal of plants and animals from the Park is strictly forbidden.