THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD IN KANSAS

“In the 1830s, a frustrated slave hunter was said to have remarked that his slaves had disappeared into thin air somewhere near Newport, Indiana. The slave hunter, so the story goes, reckoned that his slaves must have taken a ride on some sort of railroad that ran underground. How else could he explain how quickly his runaways had disappeared—with the speed of a train—or how silently they had traveled—as if they were underground. The slave hunter was wrong, but the name stuck.

“In the 1830s, a frustrated slave hunter was said to have remarked that his slaves had disappeared into thin air somewhere near Newport, Indiana. The slave hunter, so the story goes, reckoned that his slaves must have taken a ride on some sort of railroad that ran underground. How else could he explain how quickly his runaways had disappeared—with the speed of a train—or how silently they had traveled—as if they were underground. The slave hunter was wrong, but the name stuck.

The “Underground Railroad” had no rails or train cars. It didn’t travel under the ground. Instead it was a network of people who worked together to hide and transport runaway slaves on their journey north to freedom.” Gwenyth Swain, President of the Underground Railroad.

It was neither underground nor a railroad, but was so called because its activities were conducted in secrecy and because railroad terms were used in the conduct of the system. It consisted of networks of “stations” kept by “conductors” or “station keepers” who provided food, shelter, and wagon transportation from one station to another along the line of travel to freedom. People were hidden in secret rooms, basements, attics, barns and other outbuildings. They were usually transported at night to avoid proslavery kidnappers.

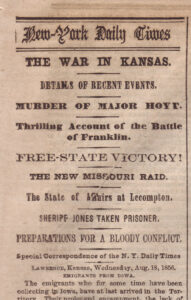

This system of individuals and safe houses operated east of the Missouri River until Kansas and Nebraska Territories were created in 1854. The legislation was the result of a power struggle between pro and anti slavery forces in Congress. A compromise was reached, allowing residents in the new territory to vote whether Kansas would enter the Union as a free or slave state. The balance of power between North and South was at stake. This ushered in the period of our national history now called “Bleeding Kansas”.

When the predominately proslavery Supreme Court of the United States decided the Dred Scott case in 1857, they declared that the main law guaranteeing that slavery would not enter the new territories was unconstitutional. This fueled the struggle that resulted in the Civil War. After the Scott decision the Underground Railroad entered a new phase. Enslaved people, and even freed blacks, began seeking their freedom in Canada. It was at this point that the Kansas Underground Railroad became most active.

When the predominately proslavery Supreme Court of the United States decided the Dred Scott case in 1857, they declared that the main law guaranteeing that slavery would not enter the new territories was unconstitutional. This fueled the struggle that resulted in the Civil War. After the Scott decision the Underground Railroad entered a new phase. Enslaved people, and even freed blacks, began seeking their freedom in Canada. It was at this point that the Kansas Underground Railroad became most active.

During these years before the Civil War, slaves seeking freedom from Arkansas, Missouri and Texas were routed through Eastern Kansas Territory.

In 1854, the only roads that existed in the territory ran between military outposts or were branches of the California/Oregon Road and the Santa Fe Trail. In the summer of 1856 Dr. Joseph Root and A. A. Jameson, members of the free state Kansas Central Committee, were appointed to lay out a road from Nebraska City, Nebraska Territory south to Topeka, a distance of about 80 miles. This was the Kansas portion of a trail that began in Iowa City, Iowa. Dr. Root was a member of the Connecticut Kansas Colony who had settled at Wabaunsee. He became a leader on the Free-State Committee when the original leaders were imprisoned.

The road was needed because proslavery forces in western Missouri had initiated a blockade that prevented free-state settlers from using the Missouri River to reach the territory. An overland route through Iowa, southeastern Nebraska and into Kansas was devised by the National Kansas Aid Committee to avoid the blockade.

When General James Lane led a large group of free-state settlers and young men inspired to save Kansas from slavery on the route it came to be known as the “Lane Trail”. The southern press called the group “Lane’s Army of the North” and portrayed them as rabble-rousers. The National Kansas Aid Committee had formed after proslavery forces sacked and burned Lawrence in May. At the time it was thought that unless free state advocates acted, Kansas would be lost to the South.

The territorial militia and federal troops, who were both proslavery, patrolled the main roads between Lawrence and Topeka. This situation made it necessary for larger and high profile “trains” to take a very circuitous route from Lawrence to southeastern Nebraska where they joined the main route of the Lane Trail that continued on to Iowa City. From there, more established escape routes were utilized through Illinois, Indiana, Ohio and Michigan, usually crossing into Canada from Detroit.